Punishment, Reward, Control: How Money Shows Up in the Business Family

In popular culture, the portrayal of family businesses in movies and TV shows, such as Ridley Scott’s "House of Gucci" or HBO’s "Succession," often revolves around the pursuit of wealth and the conflicts it incites. However, this depiction only scratches the surface of the complex dynamics at play within these families. Those of us who work with multigenerational business families can likely share a wealth of stories on how money enables families to build communities and change history through courageous investments, yet also how money can complicate family relationships and decision-making processes, fuel family conflicts, and bring to life an array of emotions ranging from shame to love.

No matter the context, money is hardly ever “just money” – a medium of exchange. When business-owning families discuss distributions or decide on family member compensation, loans, financing, valuation, or investment strategy, these conversations are often driven by the individual family members’ emotions and orientations towards money and wealth. Yet, frequently, these orientations are not made explicit, which can lead to judgement and conflict, thus eroding the fabric of family relationships.

In this short article, we share a few selected findings from our research project on money and wealth. We also provide a few pointers for family business owners, their advisors, and academics who might be interested in further exploring this topic.

What Do We Know and Observe?

Those of us who work with families understand how much a family’s orientation towards money influences their decisions – for example, underpaying or overpaying family members who work in the business, dividend policies, and loans to family members, just to name a few. However, no systematic research has focused on how and why business-owning families make different decisions related to money both in the business and in the family. Such research could serve as a solid foundation upon which to make recommendations for practice.

Our guidance, rooted in the recurring themes we encounter, therefore draws primarily from these lived experiences rather than empirical data. One of those patterns we observe in our work with families is that families frequently think that money is at the core of a conflict when in reality, the argument is centered around a deeper, underlying issue. It might simply be easier to say “I don’t think we should let our brother purchase this family heirloom at a discount” than “my parents have always loved him more so I won’t let him have this.”

We also observe that wealthy families often use money towards a certain end. They might, for example, attempt to incentivize certain desired behaviors (e.g., paying for certain educational paths) or financially reward family members for complying with expected behaviors (e.g., money for good grades). Others might seek to punish members for not meeting certain expectations (e.g., by cutting them off from family resources), or to exert control over their financial resources to force people to comply.

Lastly, we observe that money decisions are often fueled by emotional factors or an underlying orientation towards money. For example, when family members working in the business are paid the same regardless of their role or qualification, it may be that the family wants to treat all family members as equals – or it might be a misguided attempt to prevent conflict. When family pays a family employee above market to meet their financial needs, it may be because the family views money as a source of prestige and is hence concerned about making sure that family members can live comfortably. However, this could also mean that the family views money as a source of control and is using a financial incentive to keep the family member in the business.

Unless we understand the context of the individual family, unless we know the psychological drivers of these behaviors, we cannot formulate sensible recommendations for practice. Money scripts are one such tool that can help shed light on individual and collective financial behaviors.

What Are Money Scripts, and Why Do They Matter?

At the heart of our financial actions lie “money scripts,” a concept from the field of financial psychology that describes an individual’s core beliefs about money, which influence a person’s financial decisions. They are typically “unconscious, trans-generational beliefs [that] are developed in childhood and drive adult financial behaviors” (Klontz & Britt, 2012, p. 33), passed down through generations within families and cultures.

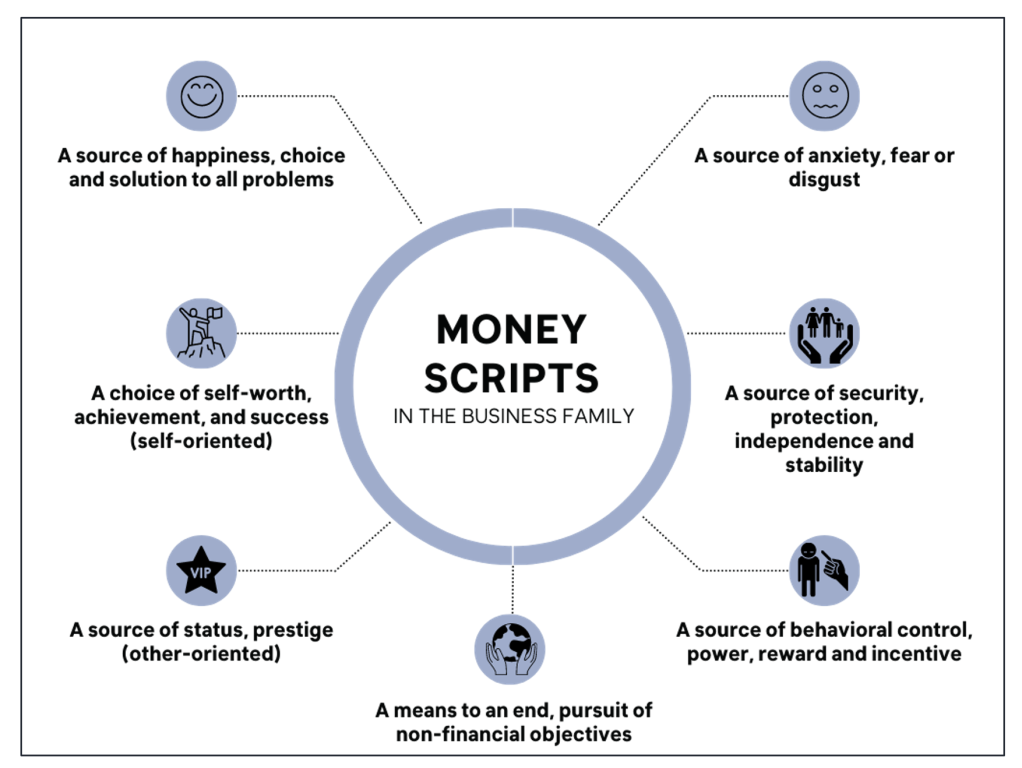

Figure 1 below illustrates the different money scripts, or the individual’s dominant orientations towards money. Money might primarily be a source of happiness, a sign of self-worth or achievement, or even a source of anxiety or shame.

Fig. 1. Money Scripts in the Business Family (based on Klontz & Klontz, 2009).

While some families may be relatively well-aligned around shared money scripts, it is more common to find large discrepancies between the money scripts of individual family members. These discrepancies can lead to conflict if families don’t recognize and talk about them, and instead judge one another for their individual financial preferences and behaviors. It can be enlightening when family members examine why they may diverge in their approaches to spending, saving, or managing risk, and in making decisions about wealth distribution. Money scripts are thus not only a tool for introspection; they can also be helpful in building empathy and fostering harmony and cohesion in the business family.

Some Research Findings

We relied on a combination of interviews with experts from the financial psychology field, with business family members, and a survey with more than 350 participants – all members of multigenerational business families from all over the world. A complete discussion of the results can be found in our comprehensive research report, but here are some interesting insights:

There is a lack of systematic education and open conversation around money and wealth in business families. As a consequence, family members do not know one another's money scripts and may resort to judging one another for different orientations towards money.

Conflicts can be conveniently masked as money conflicts, when in fact they may be centered around an underlying (likely emotional) issue. Unless the underlying issue is surfaced, addressing the superficial money issue is typically short-lived.

Money is not something we like to talk about – which may lead us to feel distanced from our friends and spouses.

Almost every other family business pays family members in the business below or above market value or pays all family members the same regardless of role or qualifications. This is often a strategy to avoid difficult conversations, which will end up driving away the best family talent.

Most business families conceptualize money and wealth as a source of security and freedom – which may affect their inclination towards investment risk or external debt.

Likely the most important finding from the survey, while not surprising, is that the quantitative methodology we applied to explore this particular topic fell short. Over the past years, we have had dozens of conversations where members of multigenerational families would talk about the burden of wealth at length: the shame and pressure that comes with being raised with the privilege of immense wealth. They would recount numerous incidents when their families used money as an instrument to incentivize, punish, or control people within and outside the family. This anecdotal evidence was not reflected in our quantitative data (however, our interview partners openly shared many stories that exemplified their often-challenging relationship with money and wealth).

Questions for Families and Their Advisors

Understanding family members’ individual money scripts can be a helpful frame to facilitate effective conversations. We all have different priorities and biases regarding money. We can talk about where they come from, or we can just acknowledge them. Where do we go from there? Can we suspend judgment?

When we fight, can we step back and consider whether an underlying emotional issue might be fueling this disagreement? Are we really fighting about money? Because if we are not, slapping a structural band-aid on the issue will just postpone a likely larger conflict.

Financial rewards are not sustainable, and they tend to backfire. If we work with a family that tends to punish or reward family members financially, can we intervene and help them think about other ways to incentivize behavior?

Money education is critical for the long-term cohesion of the shareholder group – and depending on the role, different types of financial knowledge are advisable. However, a basic understanding of financial concepts (starting with personal finance so that family members are self-sufficient in handling their financial affairs) is essential for any member of a family of wealth.

Explore the Research: It’s Not (at All) About the Money: The Many Misunderstood and Underexplored Manifestations of Money in the Business Family. Michiels, A. and Astrachan, C. (2023)

This article was first published at familybusiness.org.